[This is a cross-post from The Bookshop.ie Blog]

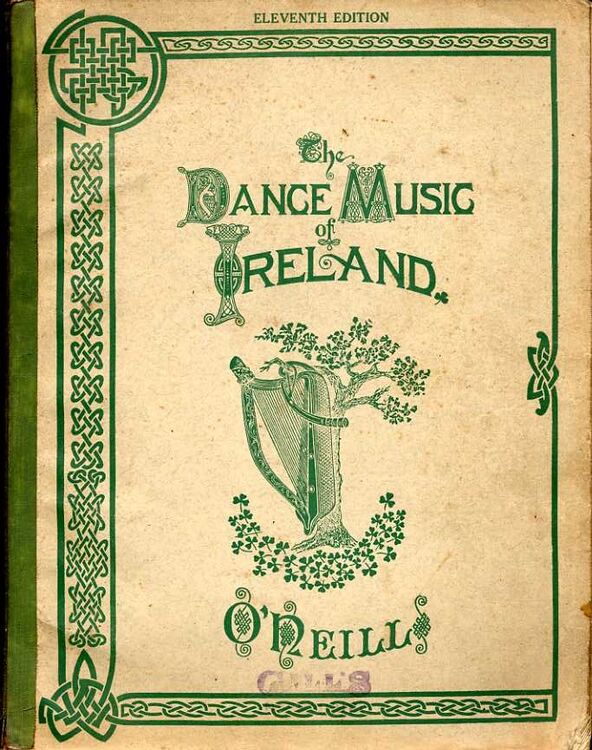

As a child in the Eighties, I came across Francis O’Neill’s 1001 Gems: The Dance Music of Ireland in our local book shop. I was in there to buy a tin whistle for school and was drawn to the celtic knotwork on the cover. My heart sank when I saw the hundreds of tunes within. Was I going to have to learn all these? I really only wanted to learn tin whistle to be able to go on a school band trip. I need not have fretted. Within a few months, I was on a very different trip with my family: emigrating to Chicago for my father’s job.

I brought the tin whistle, along with an Irish textbook, thinking I would keep on studying. Life had other plans: the jolt of leaving rural Ireland to be a teenager in Chicago proved too much, and Irish music was forgotten. Years later, after a stint as a teacher in Japan and returning to the Celtic tiger of the Nineties, I swapped my Toshiba laptop for a friend’s fiddle to take lessons in the Clondalkin Comhaltas Ceoltóirí Éireann. The teacher mentioned one of our tunes was from O’Neill’s 1001. I remembered the book from my childhood and, being a history nerd, started investigating its history.

I was stunned to find out that the man who collected the tunes had been chief of police in Chicago from 1901-1905. In all my years amongst the Chicago Irish-American community, I had missed this. O’Neill gathered the music in the Chicago of the time. In a later book, Irish Music: A Fascinating Hobby, he argued there were so many Irish immigrants that he was in a unique position to do so. His goal was to save all these tunes from being forgotten due to modernization and emigration. I felt guilty about neglecting learning Irish music properly when younger, and increased my efforts on the fiddle. I also vowed to learn more about O’Neill and ordered his memoirs: Chief O’Neill’s Sketchy Recollections of an Eventful Life in Chicago.

Within this biography, unpublished until 2008, I found strange heroic parallels to my own life. He left Bantry at the age of sixteen to travel the world. As a sailor, he survived shipwreck and near starvation on a remote tropical island. By twenty, he had circumnavigated the globe and settled in Chicago with his new wife Anna Rogers, originally from County Clare. Their timing was unlucky, as they joined many immigrants looking for work just as the city was visited by catastrophe, The Great Fire of 1871. That much I remembered from history class in high school!

Francis struggled in those early years, working as a packer in the cruel conditions of the Chicago stockyards. Tragedy visited the young O’Neill family; of their ten children, only 4 survived to adulthood. Eventually, in 1873, he received a break when hired as an officer in the burgeoning police force of the booming city. However, he was only a month “travelling beat” when shot by a criminal he still managed to arrest. He carried the bullet lodged next to his spine for the rest of his life. He went on to serve twice as police chief (the first man in Chicago to do so), all the time gathering tunes and musicians, some of whom he hired to the force.

At some point, I found myself turning the history into a novel. The story of Irish immigration was personally important, but of deeper significance was Irish music and O’Neill’s role in its preservation. Today, every city in the world has an Irish pub or two with a good chance of sessions of Irish music. Some of the people there are from Ireland, but many aren’t. What is it about this music that holds the affection of people the world over? O’Neill recognized the strong communal nature of the tradition and wanted to encourage its global spread. Today, there are young people still discovering the 1001 tunes, just as I did. Now they do so from websites and Youtube videos. My hope with Chief O’Neill is to make better known the fascinating journey of Francis O’Neill’s life.